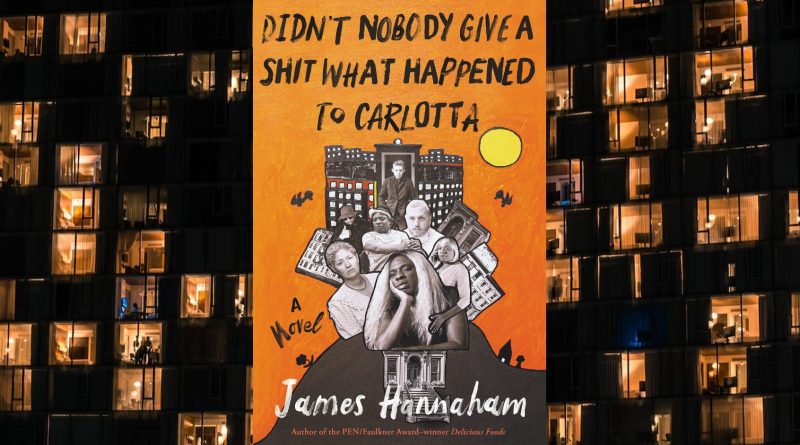

Didn’t nobody give a shit what happened to Carlotta

Didn’t nobody give a shit what happened to Carlotta is a humorous and heart-wrenching story of a transgender woman’s re-entry into life on the outside after twenty years in incarceration told over one whirlwind Fourth of July weekend.

“Everybody Black knows how to react to a tragedy,” James Hannaham wrote in his 2015 novel “Delicious Foods.” “Just bring out a wheelbarrow full of the Same Old Anger, dump it all over the Usual Frustration and water it with Somebody Oughtas. … Mention the Holy Spirit whenever possible.” In his new novel, “Didn’t Nobody Give a Shit What Happened to Carlotta,” the plot converges on a wake, and its cast of characters gleefully adhere to that pronouncement. We may understand its mechanisms, but Hannaham’s bumper-car narrative still astonishes.

Our heroine is a tragicomic character — Carlotta Mercedes is cursed with terrible timing. It’s a cruel coincidence that she ends up in a liquor store when her cousin robs the place. Carlotta happens to be carrying a gun at the time; she doesn’t fire it, but it’s not clear on the surveillance video if she points her gun at her cousin or at the cashier. She gets 12½ to 22. The judge says she’s lucky not to get more.

Carlotta doesn’t think much of luck. She is sentenced as Dustin Chambers — the name she grew up with in Brooklyn — but starts living as a woman in prison. The authorities don’t acknowledge her transition, and she is brutalized in her all-male cellblock for much of her two decades inside.

“If you want out, you better learn to talk right,” Carlotta’s jailmate boyfriend, Frenzy, tells her before her fifth meeting with the parole board. Frenzy may withhold affection, but his concern for Carlotta makes her feel “like somebody seen me, the real actual Carlotta me, the me inside me.” This is in stark contrast to the lack of letters and visitors she has received since coming out.

Getting through the parole hearing is an exercise in restraint, though Carlotta finds a way to be candid. She recounts that unlucky day in August 1993 when she ran into her cousin on the way to her best friend’s birthday party.

“Are you the sort of person who carries a loaded weapon to a birthday party?” she’s asked.

Carlotta can only reply: “I guess in Bed-Stuy in them days, there almost wasn’t really no other type of person but one who was holding. Cause the other type was called dead.”

We’re as surprised as Carlotta is when the parole board releases her, with only a year and a half left on her sentence. Now comes the hard part. “You got a son out there,” Frenzy reminds Carlotta. “Ibe.” She doesn’t need the reminder; she’s been writing Ibe weekly for 20 years, but hasn’t heard from him since he was 9.

On the bus to New York from Ithaca, she daydreams about Ibe. He’s 22 now, the same age she was when she went inside. She hopes he’s “not as nuts” as she was then. Stepping out of the Port Authority Bus Terminal, Carlotta discovers a changed city: “Not even the names of the theaters sounded familiar. One of them looked like it put on productions for children You can’t be bringing no kiddies to no 42nd Street! That’s madness! Don’t it be Drug City an Hookerville round these parts?”

Carlotta’s internal dialogue is always breaking into the third-person narrative midsentence, punctuation be damned. But her stream of consciousness keeps pace with the frenetic action of the story; her interjections feel seamless after a few pages.

“Carlotta remembered that people used the same term for coming home from prison and coming back from outer space,” Hannaham writes. “Re-entry.” When she gets to Brooklyn, members of her multigenerational Black and Colombian family don’t recognize her. Ibe has changed his African name; he goes by Iceman now. When Carlotta introduces herself to Iceman, he pleads, “Could you please, please, don’t say nothin to my dawgz?”

It’s just more bad timing that Carlotta’s release coincides with a doomed wake for a family friend at her grandmother’s house, where, in Carlotta’s words, “you could prolly wear a crotchless bodysuit outta Frederick’s a Hollywood an wouldn’t nobody bat a eyelash.” She knows she can’t participate in large gatherings where alcohol is present, but she has nowhere else to go. She ends up charming a real estate agent with a BMW, and they leave the wake for an impromptu driving lesson. (Carlotta’s only job lead requires a license and she doesn’t know how to drive.) During the lesson, in a scene out of the Marx Brothers, Carlotta spots Doodle, the friend whose party she missed when she unwittingly participated in a robbery.

The long-separated friends have a lot of catching up to do, once they’ve ditched the Beamer owner. We get more details about Carlotta’s life as a trans woman in prison, her diminishing hope at the hands of a sadistic corrections officer during six years of solitary confinement. Eventually, Carlotta brings Doodle back to the never-ending wake, where there are ugly moments with her relatives: slurs, deadnaming, taunts.

“Family,” Doodle observes plainly; we know exactly what she means.

Hannaham’s mix of humor and horror works because of Carlotta’s interjections in the narration, which have the effect of tempering catastrophe and reimagining the mundane. Notwithstanding her in-your-face tragedies, past and pending, Carlotta’s voice is captivating. Throughout the novel, she rediscovers Brooklyn and doesn’t withhold on the changes she confronts. “I ain’t seened so many white folks in one place since I watched a episode a ‘Hee Haw’ on accident,” Carlotta says. She marvels at the yoga studio that has replaced a funeral home. “You know it’s over when they doing yoga on top a Black folks’ dead bodies in Fort Greene.”

Her memories of Fort Greene and Bed-Stuy, neighborhoods that have transformed almost beyond recognition since she went to prison, may reflect the cultural backdrop of Hannaham’s own years as a queer Black writer and artist working in New York. In his fiction, Hannaham has demonstrated an abundance of empathy for the sexual minorities he writes about. Later on in the novel, he focuses our attention on Carlotta’s humiliation at being watched in the bathroom during a drug test — as she fumbles with her “Señora Problema.”

The situation unravels after Carlotta’s test. Her struggles evince an unfair and unnavigable parole system; its defects seem intractable. As onlookers to her story, we often circle the Same Old Anger, Usual Frustrations and Somebody Oughtas, but her idiosyncratic wit injects freshness and pathos to the issues.

Carlotta is irrepressible. No matter how much the prison system has abused her, regardless of the coldblooded stipulations of her parole, she is brave enough to be guided by the woman inside her tireless heart. Her instinct to follow her feminine self is as true as her bond to Frenzy and her love for her son.

Meanwhile, in real life, Gov. Greg Abbott of Texas has sought to investigate the parents of transgender children who’ve received gender-affirming medical care. Countrywide, Republican state legislators have filed almost 200 bills denying protection for trans and gay youth or curtailing discussion of L.G.B.T.Q. subjects in public schools. At a time when families with trans and gay children feel persecuted by state governments, Hannaham makes Carlotta heroic.

Don’t let the title of this wondrous novel fool you. Hannaham cares deeply about Carlotta. From a mash-up of perspectives, he writes like a guardian angel. Or — as our narrator says of Carlotta, when she’s feeling elated — “like a drag queen doing a layup.”